‘Killer Robot’ Programmer Was Prima Donna, Co-Workers Claim

Special to the SILICON VALLEY SENTINEL-OBSERVER, Silicon Valley, USA

Randy Samuels, the former Silicon Techtronics programmer who was indicted for writing the software that was responsible for the gruesome ‘killer robot’ incident last May, was apparently a ‘prima donna’ who found it very difficult to accept criticism, several of his co-workers claimed today.

In a free-wheeling interview with several of Samuels’ co-workers on the ‘killer robot’ project, the Sentinel-Observer was able to gain important insights into the psyche of the man who may have been criminally responsible for the death of Bart Matthews, robot operator and father of three small children.

With the permission of those interviewed, the Sentinel-Observer allowed Professor Sharon Skinner of the Department of Software Psychology at Silicon Valley University to listen to a recording of the interview. Professor Skinner studies the psychology of programmers and other psychological factors which impact upon the software development process.

“I would agree with the woman who called him a ‘prima donna’,” Professor Skinner explained. “This is a term used to refer to a programmer who just cannot accept criticism, or more accurately, cannot accept his or her own fallibility.”

“Randy Samuels has what we software psychologists call a task- oriented personality, bordering on self-oriented. He likes to get things done, but his ego is heavily involved in his work. In the programming world this is considered a ‘no-no,’” Professor Skinner added in her book-lined office.

Professor Skinner went on to explain some additional facts about programming teams and programmer personalities. “Basically, we have found that a good programming team requires a mixture of personality types, including a person who is interaction-oriented, who derives a lot of satisfaction from working with other people, someone who can help keep the peace and keep things moving in a positive direction. Most programmers are task-oriented, and this can be a problem if one has a team in which everyone is task-oriented.”

Samuels’ co-workers were very reluctant to lay the blame for the robot disaster at his feet, but when pressed to comment on Samuels’ personality and work habits, several important facts emerged. Samuels worked on a team consisting of about a dozen analysts, programmers and software testers. (This does not include twenty programmers who were later hired and who never became actively involved in the development of the robotics software.) Although individual team members had definite specialties, almost all were involved in the entire software process from beginning to end.

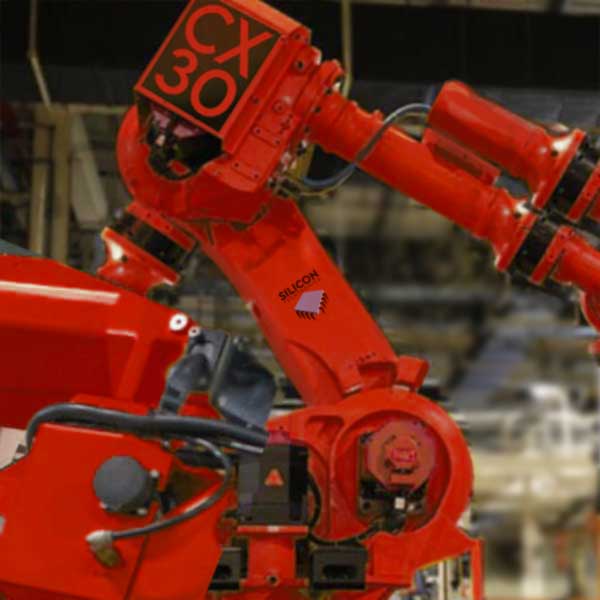

“Sam Reynolds has a background in data processing. He’s managed several software projects of that nature,” one of the team members said, referring to the manager of the Robbie CX30 project. “But, his role in the project was mostly managerial. He attended all important meetings and he kept Ray [Ray Johnson, the Robotics Division Chief] off our backs as much as possible.”

Sam Reynolds, as was reported in yesterday’s Sentinel- Observer, was under severe pressure to deliver a working Robbie CX30 robot by January 1 of this year. Sam Reynolds could not be reached for comment either about his role in the incident or about Samuels and his work habits.

“We were a democratic team, except for the managerial guidance provided by Sam [Reynolds],” another team member observed. In the world of software development, a democratic team is a team in which all team members have an equal say in the decision-making process. “Unfortunately, we were a team of very ambitious, very talented — if I must say so myself — and very opinionated individualists. Randy [Samuels] was just the worst of the lot. I mean we have two guys and one gal with masters degrees from CMU who weren’t as arrogant as Randy.”

CMU refers to Carnegie Mellon University, a national leader in software engineering education.

One co-worker told of an incident in which Samuels stormed out of a quality assurance meeting. This meeting involved Samuels and three ‘readers’ of a software module which he had designed and implemented. Such a meeting is called a code review. One of the readers mentioned that Samuels had used a very inefficient algorithm (program) for achieving a certain result and Samuelson “turned beet red.” He yelled a stream of obscenities and then left the meeting. He never returned.

“We sent him a memo about the faster algorithm and he eventually did use the more efficient algorithm in his module,” the co-worker added.

The software module in the quality assurance incident was the very one which was found to be at fault in the robot operator “murder.” However, this co-worker was quick to point out that the efficiency of the algorithm was not an issue in the malfunctioning of the robot.

“It’s just that Randy made if very difficult for people to communicate their concerns to him. He took everything very personally. He graduated tops in his class at college and later graduated with honors in software engineering from Purdue. He’s definitely very bright.”

“Randy had this big computer-generated banner on his wall,” this co-worker continued. “It said, ‘YOU GIVE ME THE SPECIFICATION AND I’LL GIVE YOU THE COMPUTATION’. That’s the kind of arrogance he had and it also shows that he had little patience for developing and checking the specifications. He loved the problem-solving aspect, the programming itself.”

“It doesn’t seem that Randy Samuels caught on to the spirit of ‘egoless programming,’” Professor Skinner observed upon hearing this part of the interview with Samuels’ co-workers. “The idea of egoless programming is that a software product belongs to the team and not to the individual programmers. The idea is to be open to criticism and to be less attached to one’s work. Code reviews are certainly consistent with this overall philosophy.”

A female co-worker spoke of another aspect of Samuelson’s personality — his helpfulness. “Randy hated meetings, but he was pretty good one on one. He was always eager to help. I remember one time when I ran into a serious roadblock and instead of just pointing me in the right direction, he took over the problem and solved it himself. He spent nearly five entire days on my problem.”

“Of course, in retrospect, it might have been better for poor Mr. Matthews and his family if Randy had stuck to his own business,” she added after a long pause.

by Mabel Muckraker

by Mabel Muckraker